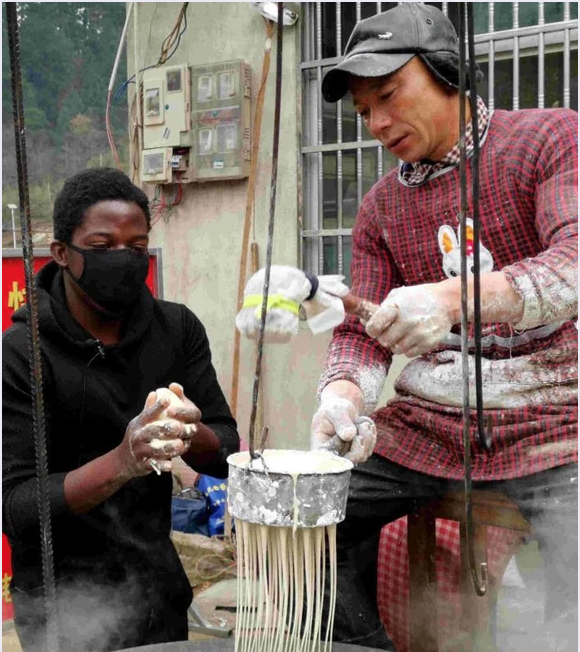

Albert Mhangami studies poverty alleviation efforts in rural China.

By CHARITY NYARAYI MATIZANADZO

Global Business Journalism reporter

The Chinese government announced in December 2020 that it had fulfilled its pledge to eradicate nationwide extreme poverty, meeting a goal set by the ruling Communist Party in 2012.

This “miracle,” as it was described by many Chinese commentators, saw nearly 100 million rural people and 832 counties emerging from poverty over the eight-year campaign, according to Chinese President Xi Jinping.

China’s victory lap has been experienced first-hand by Tsinghua University’s international students including Albert Mhangami, a second-year master’s student in the Chinese Politics, Foreign Policy, and International Relations program.

“Poverty alleviation is a global challenge that we as a global community have thrown so many tactics at and seen progress that quite simply wasn’t enough,” said Mhangami. “But, China’s success broke these standards and created a whole new level of hope that was worth engaging.”

The 27-year-old Zimbabwean citizen who has traveled to Chongqing and Anhui, first embarked on a field research trip with his department. His second onsite visit to study the poverty alleviation efforts of his host country was with Xinhua News Agency.

“I came as a stranger but they treated me as a guest,” remarked Mhangami. “Carrying the Tsinghua banner, definitely created an unwarranted level of kindness.”

Mhangami discovered that the anti-poverty strategies he had studied were “definitely evident, but the effect and interconnectedness of the policies were so different in person.”

Albert Mhangami studies poverty alleviation efforts in rural China.

Mhangami talked about his onsite experiences in different parts of China in a recent interview. Here are some highlights:

Q: What was your traveling experience like, since you were with nationals from other countries?

A: The Chinese colleagues outnumbered us quite noticeably, so the international dynamic was minimal. This was particularly helpful considering our research needed us to make people as comfortable as possible.

Q: Did the residents’ experiences help you understand the level of development in China?

A: Yes. There was a moment I walked into a home on one of the farms and realized that not only did I have a strong internet connection, so did they. They were able to engage in not just e-commerce but be part of the larger Chinese community.

Poverty often alienates communities from the national identity, and the provision of the internet provided remarkable unification by letting them be part of everyday dialogue and debates.

Q: Can you describe the state of the provinces and how they evolved from the ones you are used to back home?

A: China is more relatable to SADC [the Southern African Development Community] than to one country, and even then, a one-to-one comparison [with Zimbabwe] is impractical.

But, what I have noticed is people are the same. Those in poverty are experiencing raw human experiences, and the commonness of humanity is visible and almost identical no matter where poverty is taking place.

Q: How is the internet helping farmers like Zhang Chuanfeng engage with his audience?

A: The internet has let him expand his entire market access and product placement. He uses 抖音(TikTok) and淘宝网 (Taobao) to reach new markets and gain a loyal market base. This acts as his advertising base for his products as well as for the unique products and culture of Anhui.

Q: How is the internet helping Chuanfeng increase his income and has it succeeded in transforming his image?

A: It has resulted in new flows of income for him, a number of municipal awards and credit increase allowing him to build a house for his parents and himself. [It has also earned] him a bit of a celebrity status in the surrounding villages.

Q: Should Tsinghua University continue encouraging students to partake in these kind of research field trips?

A: I would say yes. China is hard to understand, and an easier ways to connect foreigners to China’s goals and ambitions is through people-to-people encounters.