by Alexis See Tho

The thwack of a cleaver slicing on a wooden block and the smell of fresh coffee fill the air. A hissing cloud of boiling water escapes from a wok steaming traditional Chinese buns.

It’s 7 a.m. at Jiaxin Guesthouse in Pingyao City in rural Shanxi Province. The guesthouse is 700 meters away from one of China’s last well-preserved ancient city walls. Tourists from near and far flock to this UNESCO World Heritage Site every day to witness the majesty of China’s ancient civilization. And ready to receive the hordes of tourists is Jiaxin Guesthouse.

Aihong in Jiaxin Guesthouse, which means “home” and “heart” in Chinese. Photo by Alexis See Tho.

Li Aihong, 36, and her husband are the guesthouse’s owners. The house sits on Aihong’s family land and was previously their own private home. Seven years ago, the couple built a two-story house on the family land given to them by Aihong’s father.

This husband and wife team came up with the idea to open a guesthouse during the rapid rise in tourism to China in the early years of the 21st century, culminating in the 2008 Summer Olympics. Pingyao was being discovered by the outside world, and they thought they could ride the wave of tourism to a brighter future. They figured that the land was too big for their family anyway, and Aihong had been a tour guide for years.

“My husband and I know the ins and outs of the ancient city,” Aihong said with a beaming smile.

Launching their venture

In 2010, Aihong had just given birth to her second child, Little Tiger, and thought that running a guesthouse would give her more time to spend with her son. “We’re not as lucky as other couples who have their parents take care of their children,” she said. Both her parents and her in-laws live in faraway rural villages and are in poor health.

It’s now 7:30 a.m., and Aihong has breakfasts prepared for two guests who will catch a morning train out of Pingyao. She served them yoghurt with oats and fresh banana, a kind of yoghurt parfait. It’s not a common breakfast in Pingyao, which has preserved much of China’s traditional customs and way of life for centuries. The locals eat steamed buns with vinegar-pickled cabbage for breakfast. It’s not unusual to see a shepherd herding his sheep across a busy main street.

But Aihong’s yoghurt parfait isn’t exactly Western either. It’s an invention born out of her limited understanding of Western breakfasts and the scant supply of Western ingredients in the city. Her other Western breakfast on the menu consists of a slice of white bread, a fried egg, and black coffee. She only added butter and jam after her guests told her that Western breakfasts usually include them. Nevertheless, her two European guests loved their yoghurt parfait. “Breakfast was really good,” they said, before thanking her for a wonderful stay.

Aihong quickly feeds Little Tiger a fried egg. He’s 7 this year and needs to be at kindergarten in a few minutes. She walks him to the guesthouse entrance and waves goodbye to her precious young son – Aihong and her husband wanted to have a son for years after having their first child, a daughter, who is 14 this year. Little Tiger totters out to the street on his own, walks past the house on the left that belongs to his aunt and uncle, and arrives at his kindergarten at the end of the street.

The floodgates open

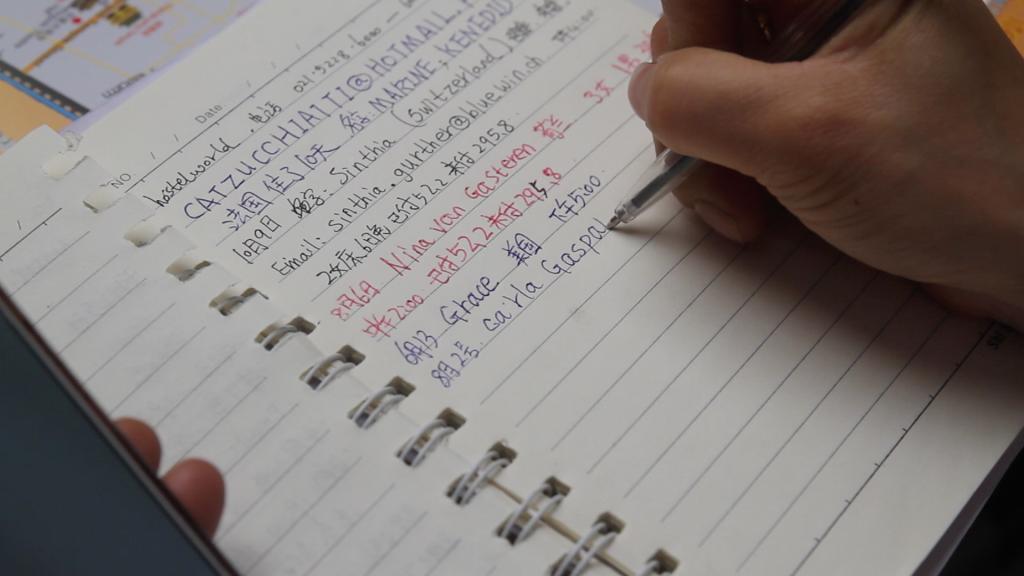

When Aihong started the guesthouse, she and her husband would wait for walk-in customers. “But we soon realized that we can’t just sit around and wait,” she explained. “So I went online.”

For Pingyao guesthouses, online booking was furthest choice from the usual business practice. But Aihong tried her luck and opened an account on Qunar.com, a leading Chinese hotel booking site. The floodgate of tourists opened.

“After going online, we were so busy that we were full almost every night,” she said. Her neighbors say her guesthouse has good feng shui, a Chinese belief in harmonizing people and buildings with the environment.

But good guest numbers don’t always translate into profits. Aihong and her husband, like many Pingyao folks, charge an honest price. A dormitory bed goes for 28 yuan per night and a private room for two is 78 yuan, or half the price of the going-rate of other guesthouses.

Aihong jots down names of guests who booked through HostelWorld in a small notebook. Photo by Alexis See Tho.

Aihong charges less because her guesthouse is located outside the main tourist area. She could earn more by raising her prices, but, she says, “We earn enough.” she said.

What’s more, she adds, ““I really like this job. We have a job that allows us to spend more time with our family.”

Before the guesthouse, Aihong’s husband was a traveling clothes salesman in neighboring rural villages. “Every time he came home, he would say he sold only a few shirts. So I told him not to go back to those villages again,” she said.

Running a guesthouse has taken a toll on Aihong’s sleep. She usually starts her day at 7 a.m. and works until 10 in the evening, sometimes even past midnight, waiting for late check-ins. Online, she advertises that her guesthouse offers “24-hour front desk for your convenience.” That means her. She’s the front desk receptionist, bookkeeper, cook and housekeeper.

At times, her dedication to her customers complicated her family life.

“Sometimes I don’t have time to look after my kids,” she said. “My daughter complains that I make breakfast for the guests but don’t have time to make breakfast for her.”

Aihong helps Little Tiger practice Chinese flute during her down time in the afternoon in the guesthouse. Photo by Alexis See Tho.

Most of Aihong’s guests these days are foreign travelers, but it wasn’t always the case. A few years ago, she realized more and more guesthouses sprung up as Pingyao became a popular tourist spot. Competition grew fierce and she started feeling the pinch. Once again, Aihong took a risk and went for foreign tourists.

In China, government regulations require lodging businesses to apply for a permit to take in foreign guests. Aihong and her husband applied for the required documents and joined Booking.com. She’s also registered on Hostelworld.com, a popular booking site for backpackers.

Learning English

She remembers her first foreign guest well: a “really tall and really big lady” from Argentina. But Aihong had a problem. She didn’t speak English. Before she dropped out of school at 15, the teacher had only taught the English alphabet and phonics. Her exchanges with the Argentinian guest involved mostly body language and Aihong’s translation app on her smartphone.

She survived hosting the first foreign guest, and over the past few years, she spent her free time learning English using Duolingo and asking the occasional Chinese guest for ad-hoc English classes. One such guest wanted to help her so much that he suggested she get an espresso machine for her foreign guests who need a cup of black coffee in the morning. She got one and learned how to grind coffee beans and pull an espresso shot.

Her family occupies a simple room of 270 square feet on the first floor. It has a bed, a TV and a cupboard. Aihong rarely leaves the guesthouse. She has never left China. But when she hosts foreign guests, it’s as if she has traversed the four seas and seven continents in the world because her foreign guests bring her news from where they come from.

Thank you notes and postcards from Aihong’s guests over the years. Photo courtesy of Li Aihong.

“They are different from the Chinese tourists,” Aihong said of the foreign tourists who stayed at her guesthouse. “Whenever I bring them coffee, they say thank you; when they leave, they write me thank you notes.”

Last summer when Aihong went traveling, she brought back bottles of Jack Daniels, vodka and neon-colored sugar syrup. After conquering the espresso machine, her next challenge is bartending.

“I see having a guesthouse as a long-term job for us,” Aihong says. “I can’t see myself doing anything else.”