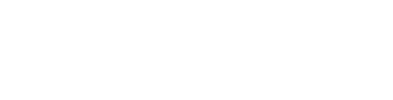

Tom Orlik, Bloomberg's chief Asia economist, predicts annual growth in China's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of 5.5 percent by 2020. By Tharnin Amnueypol.

For those concerned about a potential financial collapse in China, Bloomberg Chief Asia Economist Tom Orlik has a clear message: Do not panic.

Global skeptics have been raising flags about China's worrisome debt and slowing Gross Domestic Product growth for years, but speaking to business journalism students at Tsinghua University on Nov. 27, Orlik said the picture is brighter than some make it out to be.

He predicts an annual GDP growth of 5.5 percent by 2020 –lower than the heady days of double-digit growth, but still good enough for Chinese policymakers looking to build a "moderately prosperous society." As for its debt, the country is in a good position, said Orlik, author of Understanding China’s Economic Indicators, a guide to working with China's economic data.

"China has a bunch of things that make it easier to solve the problem" of debt, said Orlik, who is also the former chief China economics correspondent for The Wall Street Journal.

In past large-scale financial crises —— in Greece, for example —— countries with lagging GDPs took out huge loans from foreign nations, which then pulled their money out when warning signs started piling up. Orlik explained China is different because most of its borrowing has been domestic.

"Chinese households haven't got anywhere to put that money," Orlik said. "They can't take it out of the country easily. That means no one is going to be pulling the money out of the banks, so the trigger for a financial crisis isn’t there."

Student Ekaterina Kuznetsova takes notes on Tom Orlik's presentation to report the story in Tsinghua's Global Business Journalism Program. By Narantungalag Enkhtur.

However, Orliksaid that China has still created a precarious situation for itself. As he described it, the problem has its roots in the 2008 financial crisis. Western investment in China began drying up around that time, and itching to keep its momentum, China turned to internal loans to drive growth. At the same time, its GDP growth slid from a high of 14.2 percent in 2007 to 6.7 percent last year, resulting in a massive increase in the ratio of debt to GDP.

Deleveraging, or reducing debt, is "going to be painful," Orlik said, but that is the sensible solution. Countries can accumulate debt with few negative side effects in the short term, but when shaving debt, they risk also reducing wage growth, housing prices and shareholders’ equity in companies. Now that China has the world’s second-largest economy and is pouring capital into foreign countries through initiatives such as Belt and Road, any hiccups in deleveraging could affect economies globally.

"When we deleverage, we have to do it in a cautious and incremental way," Orlik said.

He expects the process to really kick in next year. Chinese leaders have indicated they are serious about taking steps toward reform, abandoning discussion of long-term GDP growth targets during October's 19th Communist Party Congress and tempering their pronouncements about the Chinese economy.

Growing so fast for so long, China must now come back down to earth.

"I hope for a soft landing," Orlik said. (By Graham Dickie)

Tsinghua students in the Global Business Journalism Program swarm speaker Tom Orlik, Bloomberg's chief Asia economist, to take his photo. By Li Dongxiao.