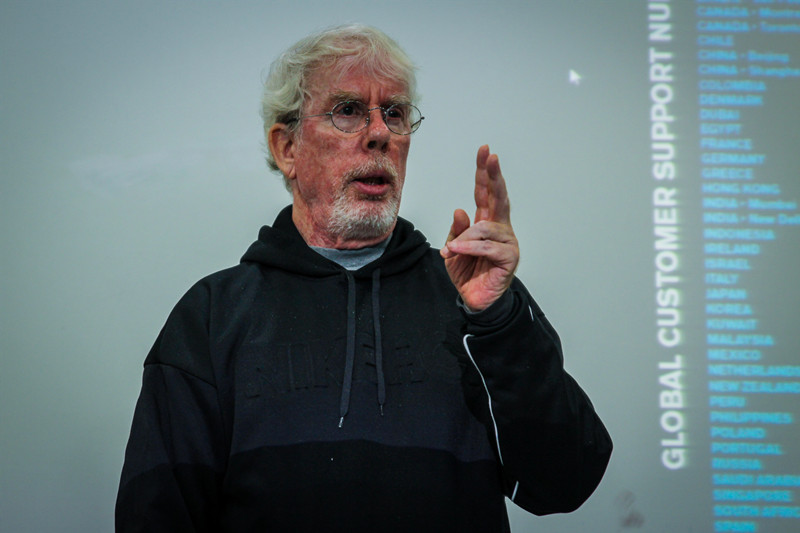

By NICO GOUS

When you are a journalist at a wire service, you are always on deadline.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve gone to a news conference and the local reporter says, ‘Ah, busy day for me. I’ve got two stories to do.’ OK, dude. At the AP [Associated Press], in one day, you could do 50 [to] 75 stories … You’ll do so many stories, when you go home, you won’t remember [them],” veteran US journalist Patrick Casey told journalism students at Tsinghua University’s School of Journalism and Communication on Oct. 29.

“You’re always on deadline. Always. As soon as you get a story, start working on it. If I give you a story and I see you get up, go get some coffee, maybe get on WeChat, aargh, don’t. Don’t do that.”

As a reporter for the largest U.S. wire service, Casey covered the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, in which Timothy McVeigh killed 168 people by exploding a truck bomb in front of the federal courthouse. He has lived in Beijing for the past 11 years.

How do you cover big or traumatic stories? Take a deep breath, don’t think about what you’re seeing, do your work, and don’t cry, Casey said.

“You cannot help but be affected. You can’t. But later, not then,” he advised the students.

One of Casey’s tasks when covering the Oklahoma City bombing was to call the bureau when authorities removed a corpse from the bombsite to update the death toll.

“The wind would blow towards us, towards the media centre, the smell of death, you could smell it, dead bodies,” Casey said.“When you cover something like the bombings, something so major, it’s just a blur. A lot of it is just a blur and you just do what you can.”

On Sept. 11, 2001, Casey and his colleagues saw CNN’s initial,inaccurate report that a small airplane crashed into the World Trade Center. At first they thought the pilot must have been stupid to fly into the skyscraper. But moments later, the reality of the situation became clear to Casey and his AP colleagues.

“We walked over to the TV and we’re trying to figure out how much damage a small airplane can do to a big building,” he recalled. “We’re thinking maybe a floor or two. And then, all of a sudden, you see the second plane, BOOM. We’re like: ‘Holy sh*t. What is this?’

“I’m thinking: ‘Wow! This is a damn busy day’ … It was just unbelievable. I can’t begin to tell you.”

Reports started coming of another plane crash. No one in the newsroom connected the dots to the plane which crashed into the Pentagon until later. Casey said when you’re covering a big story, you’re so focused on what you’re doing that you sometimes can miss the big picture.

“A couple of hours in, we knew it was bad,” he said. “We thought maybe there were going to be more targets in New York. It could have been the Rockefeller Center. It could have been the Empire State Building. It could have been the subways. It could have been anything. Nobody knew.

“To be honest, I can’t remember everything, because it’s just a blur. To this day, it’s just a blur.”

Casey said the Oklahoma City bombings, where dozens of children were killed in a day-care center inside the courthouse building, affected him more emotionally than the 9/11 attacks that killed 3,000 civilians and firefighters.

“For me, the [World] Trade Center was an act of war. It was war. You react differently to it,” he said. “It’s not like 50 kids got blown up by a bomb. That’s heart-breaking.”